By Roger Sandilands, Emeritus Professor of Economics, Strathclyde University

and Fred Harrison, Director, Land Research Trust, London.

PDF version: potsofgold.web

Scotland can strike out on a new path to social renewal and realise the SNP goals of enhancing people’s lives and abolishing inequality

The stunning triumph of the Scottish National Party in the general election of May 2015 reinforced the need for tax reform. Without pro-growth changes to taxation, Scotland will be dragged by Westminster’s fiscal policies into UK-wide recession by 2019. And Conservative ‘austerity’ policies will continue to weaken Scotland’s economy and society.

The Conservative UK Government may now seek to trap the SNP with the offer of full fiscal autonomy, believing that this would cause havoc with Scottish finances. This would be a serious political miscalculation. For even under the devolved fiscal powers proposed through the Smith Commission, Edinburgh can cut Income Tax in 2017 and boost the economy to the tune of billions of additional pounds. Investors starting up new businesses would turn to Scotland. And by raising revenue from land rents under a reformed property tax, the incentive to speculate in land – the primary driver of the business cycle – would be moderated.

Scotland can now strike out on an independent path to social renewal to achieve the SNP’s goals of enhancing people’s lives and abolishing inequality.

An independent vision

A sizable proportion of the people of Scotland vested their trust in the Scottish National Party at the referendum in September 2014. Many who voted against formal independence from the United Kingdom have nevertheless registered their desire for change. Following the financial débâcle of 2008, the status quo is no longer acceptable. That is the lesson of the May 2015 General Election.

In March 2015 the SNP Government issued a document to chart the way forward. Scotland’s Economic Strategy was presented as a step-change away from conventional policies, thereby highlighting the route towards a progressive society.

Few would disagree with the objectives set by the Scottish government. The goal is a vibrant and diversified economy which is fair and unites all sections of society. Priority is given to investment and innovation to create inclusive growth. This is the vision held out by the first Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, in her foreword. The concepts are familiar: sustainability, fairness, national prosperity.

Unfortunately, the plan conforms to the legacy of an economic paradigm which necessarily generates long-term unemployment, sustains barriers to personal development and creates obstacles to the renewal of communities.

The word sustainable is borrowed from ecologists and is now applied to practically every political pronouncement. But we now have sufficient evidence from economic history to know that the capitalist economy, as at present constructed, operates on the basis of 18 year business cycles. These are structured around boom/busts in the property market. The dynamics are to be found in the way land markets distribute income and raise expectations about capital gains that lead to destructive bouts of speculation. These are followed by protracted periods of unemployment (Harrison 1986, 2005). Scotland’s Economic Strategy offers no antidote to this disruptive process.

The taxing question

The SNP complains that it has not been accorded sufficient power in the post-referendum settlement. However, its control of income tax rates provides the Scottish government with a tool that could lead to a doubling of Scotland’s growth rate, re-lay the foundations of the labour market on principles of equity and natural justice, and attract entrepreneurs who wish to establish new businesses in a labour-friendly environment.

To understand why current policies and proposals will not stabilise the Scottish economy, we need to understand how taxes both discourage and distort economic activity. For historical reasons, they misdirect the employment of land, labour and capital. Fortunately, the Scottish Government has been empowered by the terms of the Smith Commission to significantly restructure the public’s finances. The SNP claims that

“For the Scottish Parliament to be able to create jobs and tackle inequality, it needs more than control over one or two taxes. It needs control over a range of taxes, both personal and business. It needs control of key economic levers like employment policy”.

We shall show that, by exploiting existing devolved powers to the maximum, the Scottish Parliament can trigger a momentum towards prosperity to create significant benefits for everyone in Scotland.

A manifesto for emancipation

By understanding the scale and nature of the damage inflicted on them by the taxes levied by government, people can begin to visualise the enormous benefits they can achieve with fiscal reform. Conventional taxes are the legacy of the lairds. They are arbitrary, invasive and discriminatory.

The alternative for Scotland is replacement of taxes on earned incomes with a unique charge on unearned economic rents. This would lay the foundations for the democratisation of the public’s finances. The cornerstone principle is that people should be free to keep what they create, and pay for what they receive.

Embedded inequality

It is true that Scotland is tied to ‘an economic model that has exacerbated inequalities’. Of the 34 OECD countries, the UK ranked 29th in terms of income inequality. The disparity in the distribution of income is the logical outcome of the way in which government fiscal policies favour the activity which economists call rent seeking.

Rent seeking

The original rent seekers were the lords and lairds who enclosed the common and clan lands so that they could capture the rents produced by people whose status was converted to that of tenants. Since then, rent seeking has been extended to include those with power in the banking sector, and those who are able to influence public policies in a way that privilege them against their fellow citizens. Ultimately, the economic gains accruing to these sections of society come out of what economists call economic rent.

Economic rent

Classical economists like Adam Smith divided national income into three categories:

- the wages of labour

- the profits from man-made capital that was created to assist in the value-creating process, and

- the remaining or net income, which was called economic rent.

In a society that was both fair to everyone, and efficient in the production of new value, wages and profits would remain in the hands of those who worked for their living. But the net income – the economic rent that exists after wages and profits have been paid – needs to be treated as unique. It is a composite value that reflects the services of both nature and society. Therefore, as Adam Smith pointed out, this was the proper source from which to fund public services (Smith 1776: Bk V, Ch. II, Pt. II, Art.I).

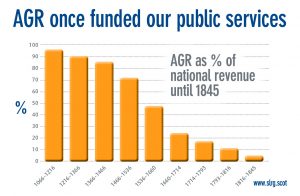

Historically, under the feudal and pre-feudal forms of social organisation, the State was funded out of that net income produced by the population. In England, for example, we have the data which demonstrates that the state created by William the Conqueror in the 11th century was wholly funded out of the rents generated by the agriculture-based economy (Graph 1).

Taking control

It all started to go wrong as the feudal aristocracy decided they had a special entitlement to that rental revenue. They embarked on a historic transformation of the English Constitution so they could take control of the public finances away from monarchs. Their intent was to reduce the revenue collected by the land tax, so that they could pocket the rents themselves. The reciprocal was the invention of new taxes which were directed at the peasants.

This was not just the theft of state revenue. It was also a strategy that suppressed the productive potential of the people. That was the effect of taxes on wages and consumption, and on the capital that was created by working people. As a result of tax-induced distortions, a raft of additional distortions were inflicted on communities as governments tried to manage the chaos that can be traced back to the de-socialisation of rental revenue. Those distortions restrained people’s ability to produce the incomes that were legitimately theirs.

- Taxes such as those on salt and beer, and on the windows of people’s homes, had a grinding down effect on both personal psychology and the fabric of communities.

- The privileged accumulation of rents enabled the aristocracy and gentry to evolve a culture that separated them from the rest of the people

(Thompson 1991:Ch.2).

The economics of apartheid

The Scottish government asserts that ‘everyone has a right to participate fully in society’ (p.63). It notes the growing concentration of income at the top end of the distribution scale, with what it calls the ‘highest earners’ receiving a greater share of the income in recent years.

The problem with the government’s analysis is with the way it analyses the top incomes. In common with all governments and academic analyses of income distribution, such as the widely acclaimed investigation by Thomas Picketty (2014), little attempt is made to differentiate between earned and unearned income.

- High incomes that are earned imply that the beneficiaries added value to the sum total of wealth.

- It is a different story with those who get rich on unearned income. They damage the welfare of others.

The inequality between rich and the poor, which the Scottish government says it opposes, was and remains the logical outcome of conventional modes of governance.

The outcome of the privatisation of socially-created rent is the economics of apartheid. Any attempt to correct that inequality must be viewed in terms of the historical perspective.

In the late mediaeval period when the peoples of the British Isles still relied on agriculture, whole communities were demolished and people expelled from their traditional habitats so that the rent seekers could maximise their incomes. Thus was born the deferential society, in which the peasants, and the later proletariat, were schooled into doffing their caps in acknowledgement of their ‘betters’.

This socio-economic model, which separated people into the haves and have-nots, remains with us to this day. The welfare state that was created in the 1940s could not alter this tragedy. Some of the worst excesses have been moderated through the transfer of incomes to those who have not been able to fight their way out of the grip of social exclusion. But the propensity remains: to recreate a new subclass with every generation. And the policy of taxing the incomes of those in work has added to the discriminatory nature of the fiscal regime; in the process, it has added to loss of national wealth and welfare. This was not what Adam Smith envisaged for his native Scotland (see Box 1).

Box 1. Adam Smith’s ‘peculiar tax’

“Both ground-rents and the ordinary rent of land are a species of revenue which the owner, in many cases, enjoys without any care or attention of his own. Though a part of this revenue should be taken from him in order to defray the expenses of the state, no discouragement will thereby be given to any sort of industry. The annual produce of the land and labour of the society, the real wealth and revenue of the great body of the people, might be the same after such a tax as before. Ground-rents, and the ordinary rent of land, are, therefore, perhaps, the species of revenue which can best bear to have a peculiar tax imposed upon them.” (Smith 1776:Bk.V: 370; emphasis added).

A modern manifestation is the enrichment of homeowners, who have capitalised on their good fortune with wealth untold, at the expense of the new generation. Young adults now find it increasingly difficult to establish families and secure a foothold in labour markets.

The democratic deficit

During the general election campaign of 2015, the SNP focused attention on its determination to abolish inequality by administering a ‘tax system that is fit for the 21st century’ (SNP 2015:14). The puzzle, however, is that it proposed to retain the existing way of raising revenue, along with some amendment to the locally-administered property tax and piecemeal ‘land reform’ in the guise of community buy-outs. On the basis of this strategy, the SNP could not realistically expect to change the course of Scotland’s social and economic development. This conclusion holds, even if the SNP government achieved ‘full fiscal responsibility’.

The SNP called such devolution of fiscal power ‘a fairer approach to taxation’. The implications were examined by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). It concluded that Scotland would endure a fiscal deficit every year up to 2020. The shortfall of revenue in 2020 would be nearly £10bn. The projection is shown in the top row of forecasts in Table 1.

The IFS projections are seriously misleading, because they do not include the offsetting gains that could be achieved from fiscal reform. To properly evaluate the claims by the SNP, the people of Scotland needed a full audit of the fiscal implications. Democratically speaking, they were entitled to some idea of the full costs associated with current funding policies. Those costs are technically called the excess burden of taxes. The more meaningful term used is deadweight losses.

Deadweight losses

Economists can measure the wealth and welfare which people forego as a direct result of the way government chooses to raise revenue. The IFS failed to provide estimates of those losses (Box 2).

Box 2. Measuring deadweight losses

In the general election of 2015, all four major political parties declared that they would have to increase taxes if given the power by the electorate. The IFS assessed and compared those increases, and concluded:

“None of these parties has provided anything like full details of their fiscal plans for each year of the coming parliament, leaving the electorate somewhat in the dark”.

Furthermore, IFS researchers said they had to make many assumptions about the parties’ real intentions in order to crunch the numbers (Crawford 2015).

The IFS, however, which is billed by the media as Britain’s authoritative independent assessor of tax policies, failed to provide estimates of the deadweight losses of those proposed tax increases. It declines to calculate deadweight losses because it would have to estimate the damage inflicted by all the marginal tax rates in what is a complex fiscal regime (Adam 2014).

Offering such estimates, no matter how proximate (after all, the IFS was willing to indulge in guesswork in order to make pronouncements on the work of others), would at least draw attention to the fact that elected representatives use revenue tools that cause losses, compared to those financial instruments which inflict no such loss on working people. This, of course, would then raise the question of whether it was possible to raise revenue without damaging the economy.

The scale of the damage caused by conventional taxes remains controversial. HM Treasury claims that the deadweight loss is equal to 30p for every £1 raised (Harrison 2006:155, 156). This is such a low estimate that it raises serious questions about the integrity of the assessment process. The 0.3:1 ratio suggests that the Treasury is only taking into account their costs of administering the tax regime, and the costs of administrative compliance by taxpayers. This excludes the distortions to behaviour that arise from the disincentives created by taxes. Some US economists claim that the total damage is as high as 1.5:1 – that is, a loss in wealth and welfare of $1.50 for every $1 collected by such taxes. The ratio that is recommended by a leading fiscal economist (Mason Gaffney) is 1:1 (Box 3).

Box 3. The Gold Standard

We base our estimates on average deadweight losses. What is sacrificed in precision is gained in public comprehension. Taxpayers are intuitively aware that there is an unaudited loss associated with the taxes they pay, but they have no concept of the society-wide scale of the losses inflicted by their elected representatives. Politicians bombard them with value judgements like ‘fair’ taxes, but such words are plastic. They are manipulated to mean whatever is required by each political ideology.

What is not controversial, however, is the gold standard against which the damage caused by tax policies must be judged: When revenue is collected from economic rent, damage is not inflicted. In fact, rent-charging tools must be characterised as ‘better than neutral’ (Tideman 1999; similar insights are in Feldstein 1977). That is because they positively support behaviour that increases people’s wealth and welfare. Here is how one economic textbook explains the point:

“Land will not be forced out of use, because land that is very unprofitable will command little rent and so pay little tax. Thus there will be no change in the supply of goods that are produced with the aid of land, and, since there is no change in supply, there can be no change in prices. The tax cannot be passed to the consumers.”

(Lipsey 1979:370; emphasis in original)

By eliminating the losses inflicted by ‘bad’ taxes, society enjoys a net gain from switching to charges that fund public services out of socially-created economic rent. Productivity is improved in a million and one ways.

- When people are not taxed on earned incomes they may choose to earn more because the additional income does not attract the attention of the taxman. Alternatively, they may choose to receive the benefit in the form of more leisure time.

- Investment in capital goods would increase and be employed more efficiently. Under the current regime, capital is diverted to ‘tax efficient’ projects which may not maximise the satisfaction of consumers, but which minimise the taxes paid by corporations.

Under the rent-revenue formula for public finance, labour and capital resources are devoted to optimising the satisfaction of people who want the goods or services that are made available in the economy. Consumer satisfaction is synchronised with the objectives of the producers.

Here we identify just two of the virtues of the rent-revenue strategy.

• The policy of abolishing harmful taxes is self-funding

As taxes that damage the nation’s health and wealth are reduced or terminated, the rentable value of “land” in all its forms rises by corresponding sums. This is explained by the ATCOR thesis – All Taxes Come Out of Rent. The theory was originally elaborated by John Locke in the 17th century, documented in the 18th century by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, affirmed by John Stuart Mill in the 19th century, and received its most exhaustive treatment in the 20th century in the studies by Mason Gaffney, Professor of Economics at the University of California. The political implications of this insight are of major significance: it means that, in abolishing harmful taxes, current public services do not have to be sacrificed. This contrasts with the austerity programme pursued by governments post-2008 in which, to cut budget deficits, taxes had to be raised or services reduced.

• The public’s finances are democratised by the rent-revenue policy

People exercise the power over when, why and how they fund the services they want to use. This is the case today, for example, in the housing market. When someone chooses the location where she wishes to live, she selects a home on the basis of two criteria.

1. The merits of the building are evaluated: whether it has the required number of bedrooms, for example. Then,

2. account is taken of the proximity to the desired public services, such as transport, schools and parks.

The public services within the catchment area are advertised by estate agents. This is essential information, because the quality and accessibility of public services affect the price of the property.

The anomaly in this arrangement is that the part of the ‘house’ value which is paid to access the public services is not paid to the public agencies that provide the amenities. Instead, that value (the rent of location) is paid to the vendor of the dwelling. That payment exposes the pathological character of the tax regime.

Now we consider what would happen if the central government in Westminster did agree to devolve full fiscal autonomy to the Scottish Parliament. What would count as the responsible political behaviour to which the SNP wishes to adhere? May we fairly assume that SNP politicians would not wilfully employ taxes that damaged the health and wealth of the people who elected them? As a party that asserts its ‘progressive’ credentials, wouldn’t the SNP wish to replace deadweight losses with net gains? The gains could be far greater than those we have calculated, if the deadweight losses reported by some distinguished economists prove to be closer to the mark (Box 4). So how could an SNP government achieve these benefits?

Box 4. Top-end losses

Martin Feldstein is a professor of economics at Harvard who chaired the President’s Council of Economic Advisers in the 1980s. Using the marginal impact of taxes, he concluded that the damage to the US economy exceeded the ratio of 2:1 – that is, over $2 of losses in wealth and welfare were incurred for every $1 raised in taxes. His estimates began with a minimum of $0.78 per $1, assuming that a 10% increase in the tax rate increased tax revenues by 10%.* But on the more realistic assumption that a 10% increase in the income tax rate will produce significantly less than 10% extra tax revenue (because the fall in income will reduce taxes), he estimates the deadweight loss at $44/$26, or $1.7 loss per $1 raised. And if the effect on social security revenues is also taken into account, the ratio is $44/$21.4 or $2.06 loss per $1 of revenue. * Feldstein (1999:678).

• As a first step, the government could zero-rate the Income Tax. Under the powers devolved to Edinburgh in 2015, control over the Income Tax, alongside the existing control over property taxation, makes such a reform possible.

The net gains are shown in the bottom row in Table 1. Replacing the Income Tax with revenue raised through rental charges would deliver an annual net gain to Scotland of circa £11bn. Over the five years from 2016 to the Scottish elections of 2021, the people of Scotland would be enriched by nearly £60bn!

This contrasts strongly with the outcome under the existing funding arrangements, in which the people of Scotland would continue to accumulate a debt-servicing burden. By eliminating the deadweight losses caused by current taxes, the projected net gains from re-socialising rent revenues would be able to convert large annual deficits into large annual surpluses.

The SNP seeks ‘full fiscal autonomy’. According to interpretations of statements by Prime Minister David Cameron, this may be the Machiavellian strategy of the Tory Government [Giles 2015]. We see such a strategy in different terms.

Assuming the SNP government achieved such power, it could decide to get rid of regressive taxes such as VAT, National Insurance Contributions, Customs Duties – all the exactions that distort people’s decisions on spending and investing. Replacing the revenue by employing the strategy proposed in this bulletin would transform black holes into pots of gold.

In 2014, the revenue from taxes levied in Scotland which caused most damage to the economy added up to about £33bn. This excludes those charges that fall directly on rent (such as oil rents). It also excludes the revenue from ‘sin taxes’ that people may choose to retain, to deter private activities that impose social costs (such as taxes on tobacco and alcohol). If Scotland abolished the damaging taxes and instead raised the revenue from rents, the net gain in wealth and welfare in just one year would be circa £33bn.

But would there be sufficient rent to replace the bad taxes so as to retain the current level of public services? As already noted, this is not a valid way of putting the question.

Under the ATCOR thesis, all taxes come out of rent. In other words, existing taxes are already derived from the nation’s rents, but they are collected indirectly, and misleadingly labelled ‘income’ tax or ‘value added tax’. By scrapping this indirect way of raising revenue, the eliminated taxes would resurface as collectable rents. So by swapping the indirect for the direct way of collecting the rent, Scotland would be rationalising the fiscal system.

This is not a merely cosmetic adjustment. Nor is it simply a redistribution of one kind of revenue for another. Through the private and public sectors, the population would share the bonus of an increase in total income running into billions of pounds a year – no matter which measure of deadweight losses was employed.

Dynamics of the moral economy

The switch to funding policies that draw revenue directly from rent would frame the national budget within the principles of integrity, transparency, accountability and, indeed, natural law (Sandilands 1977).

Revenue from North Sea oil rents may diminish to zero over the next 40 years. But Scotland is rich in its educated labour force, which will continue to produce social rents at an increasing rate as the productivity of the economy rises under the influence of tax reform.

The only issue at stake is the quantum of rents that the government allows the population to produce. For in addition, the territory

is rich in rent-generating natural resources which include

- the radio spectrum

- highland wind

- aircraft time slots

- nature’s waste absorbing capacity

- salt water

- fresh water

- …and a long list of other natural and social resources itemised in Mason Gaffney’s inventory (Appendix 1 in Harrison 1998; and see Gaffney 2009).

A vision of Scotland’s emancipation

To appreciate the scope for transforming people’s personal lives and the fabric of the community, we need an exercise in counterfactual history. What would have happened (say) if the rent-revenue policy had been adopted back in the 1970s? How much richer would the people of Scotland have been, if the growth rate had been higher by, say, 2% per annum? This is a reasonable, cautious assumption to take as the starting point for analysis.

Box 5. The magic of freedom

The annual average growth rate for Singapore (1970-2012) was 7.6% (6% in per capita terms), instead of the more typical 1% or 2% in countries more reliant on disincentive taxation. In real terms, Singapore’s per capita income in constant US$ (base year 2011) rose from US$6,708 in 1970 to US$48,630 in 2011, a real increase of 625%. See http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/singapore/gdp-per-capita together with World Bank 2011 data: http://data.worldbank.org/country

The comparable figures for the UK were US$19,198 in 1970 and US$41,680 in 2011, a far more modest increase of 116%. This meant that the UK, initially nearly three times richer than Singapore in 1970, ended up 17% poorer by 2011. Scotland lagged behind even furrther.

Singapore

Singapore, for example, increased its economy over many years by an annual average rate of 7.6%. That is three times Scotland’s rate (Box 5). How was this achieved? According to a professor of economics at Singapore Management University, the city state flourished because the economic model contained ‘elements of [Henry] George’s land value tax capture”.1 She explained:

‘Soon after independence, the Land Acquisition Act was passed in 1966, which gave the state broad powers to acquire land. In 1973, the concept of a statutory date was introduced, which fixed compensation values for land acquired at the statutory date, November 30, 1973. State land as a proportion of total land grew from 44% to 76% by 1985 and is now around 90%.’

(Phang 2015).

Rents that accrued from growth were ploughed back into funding yet more and improved infrastructure, and taxes that damaged the economy were held down. Thus, we are entitled to take Singapore’s performance as a comparator, to gain some sense of what Scotland could have achieved – and might still achieve – if she had enjoyed similar fiscal and land-use policies (Sandilands 1992, 2015).

The 1970 real UK GDP (in 2008 prices) was £575.7bn. With the UK population at 55.6 million, this represented an average income per head of £10,555 in 2008 pounds. Over the period 1970–2012, the UK’s annual average growth rate was 2.52% (2.2% in per capita terms). By 2012, UK GDP stood at £1,414.8bn. With a population that had grown by 14.6% to 63.7 million, average income per head had slightly more than doubled to £22,211 (again in 2008 pounds). If the overall growth rate average had been just two percentage points higher over the period, at 4.52%, the real UK GDP in 2012 would have been more than 6 times greater, at £3,768.4bn. Income per head, instead of doubling, would have risen nearly six-fold, to £59,158. The difference is a very substantial sum: £36,947 per head. Such is the effect when people are freed to realise their full economic potential.

Growth provides the incentives and the wherewithal to invest in more specialised, hence more productive methods and organization. With the removal of distorting and destructive taxation, growth is accelerated. But if, as may be expected, a higher growth rate is largely self-perpetuating (in the absence of major exogenous shocks or policy errors), the gains are compounded and compounded. With her 7.6% average annual rate of growth (6% per capita) since 1970, Singapore was able, from a base income only one third that of the UK, to catch up and overtake the UK within less than 40 years. This reveals the benefits from grasping the nettle of reform, enabling Scotland to achieve a comparable ‘miracle’ relative to the UK if it were willing to embark on a justice-based fiscal reform through full fiscal devolution.

A fresh start

In Scotland’s Economic Strategy the SNP government claims that there is an advantage to be gained from amending the corporation tax in the way that it is believed the Northern Ireland assembly would do to compete with the low corporation tax that prevails in the Republic of Ireland. This ignores the sponge-like effect of the land market. Cut the income tax or corporation tax and the benefit ends up in raising the price of land. House prices would rise by an equivalent sum, thereby injecting a new round of destabilisation in the property market (as indeed was the Republic of Ireland’s experience). The winners would be those who currently own land-based assets.

The Scottish government’s strategy on land is at present confined to two policies:

1. Empowering local communities to buy their way back into land rights

There is not – and never will be – enough money to empower every community to buy land back from existing owners. Justice requires a formula that is fair to everyone in Scotland. The buyback model does not deliver that universal justice.

2. Authorising communities to acquire land in public ownership

The efficient use of land in the public domain is essential. Much of it is unused or underused. This imposes a significant and continuous burden on the population. Nevertheless, this approach to community empowerment does not lead to the dynamic model of citizen engagement of the kind that liberates everyone to fulfil his or her capabilities, freed from the shackles of dis-incentivising taxes.

Our vision of an emancipated Scotland offers new perspectives on existing government policies. The rural development programme, for example, proposes expenditure of £1.3 billion over the six years to 2020. This sum, and the associated fiscal policies, cannot in themselves override the process by which people are systematically driven away from the countryside in search of jobs in towns.

The Attainment Scotland Fund of £100 million for education and disadvantaged communities is welcome, but it lacks the punch that is needed to knock down the barriers that are endured by each new generation.

The sum of £100 million is not trivial, but is modest when compared to the riches that would flow by zero rating the income tax.

Scotland has a resource that will never be exhausted: the ingenuity of the people themselves.

- Most of the rents now generated within the borders of Scotland stem not from nature but from the cooperative activities of people working through their communities

- The agencies that provide the services that are shared in common automatically create the value that is pooled into that stream called economic rent

That is a stream which will never run dry for so long as the people are free to work. But the stream of rents can be reduced to a trickle under government policies that damage the freedom to work efficiently.

Through the ballot box the people of Scotland have registered their desire for a fresh start. Whether this is within or without the UK, there is no alternative model for social renewal than the one driven by fundamental financial reform. The history of post-communist countries is revealing.

The rent-as-public-revenue model was commended

in the early 1990s by a distinguished group of economists, including five Nobel laureates, as the cornerstone for the new market economy (Noyes 1991:225-230). The current tragedies in Eastern Europe, from Russia westwards to the Baltic countries and southwards through the Balkans to Ukraine, illustrate what happens when the rent-seeking motive is allowed to take control of culture. Oligarchs are the winners.

The lessons of post-Soviet Europe were not learnt by the Chinese Communist Party. Soon after China began to liberalise the command economy, the rent seekers moved in to inflict a similar tragedy on the people. Civil servants in local authorities, and investors who originally made their fortunes out of manufacturing, piled into real estate to enhance their personal fortunes. The result was a land boom that continues to destabilise China (Graph 2).

The people of Scotland now have a unique opportunity to scope out the strategies that will actually work for their personal and common good. By empowering their elected representatives to initiate the appropriate reforms, they would be revisiting the agenda which their ancestors mandated more than a century ago. That was when the people of Scotland took the initiative to authorise their representatives to introduce new charges on the rents of land. For a summary of that history, see the video at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHSlMFnnsC0

If Scotland once again took the lead, we believe that the other nations of the UK would follow suit – just as they did in the lead-up to The People’s Budget of 1909. This time, in the absence of the intervention of a world war, the outcome would be a material prosperity and quality of life greater than the sum of the divided parts.

References

Adam, Stuart (2014), Personal email to Fred Harrison, October 14.

Crawford, Rowena, et al., (2015), ‘Post-election Austerity: Parties’ Plans Compared’, IFS, Briefing Note 117.

Feldstein, Martin (1977), ‘The Surprising Incidence of a Tax on Pure Rent: A New Answer to an Old Question’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 85, No. 2 (April).

Feldstein, Martin (1999), ‘Tax Avoidance and the Deadweight Loss of Income Tax’. Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 81(4), pp.674-680.

Gaffney, Mason (1994), ‘Neo-classical Economics as a Stratagem against Henry George’, in Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison, The Corruption of Economics, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

Gaffney, Mason (2009), ‘The hidden taxable capacity of land: Enough and to spare.’ International Journal of Social Economics, 36:4, pp. 328-411.

Giles, Chris (2015), ‘Result raises prospect of Scottish fiscal autonomy’, Financial Times, May 9.

Harrison, Fred (1986), Power in the Land, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

Harrison, Fred (1998), ed., The Losses of Nations, London: Othila Press, Appendix 1, and essays at www.masongaffney.org

Harrison, Fred (2005), Boom Bust: House Prices, Banking and the Depression of 2010, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

Harrison, Fred (2006), Wheels of Fortune, Institute of Economic Affairs. http://www.iea.org.uk/publications/research/wheels-of-fortune

Harrison, Fred (2012), The Traumatised Society, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

Lipsey, Richard G. (1979), Positive Economics, 5th edn., London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Noyes, Richard (1991), Now the Synthesis: Capitalism, Socialism & the New Social Contract, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Open_letter_to_Mikhail_Gorbachev_(1990)

Phang Sock Yong (2015), ‘Home prices and inequality: Singapore versus other global superstar cities’, The Straits Times, April 3. http://www.straitstimes.com/news/opinion/more-opinion-stories/story/home-prices-and-inequality-singapore-versus-other-global-sup

Phillips, David (2015), Full Fiscal Autonomy Delayed? The SNP’s plans for further devolution to Scotland. London: Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), 21 April 2015. http://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/7722

Picketty, Thomas (2014), Capital in the Twenty-first Century, Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press.

Sandilands, Roger J. (1986), ‘Natural Law and the Political Economy of Henry George’, Journal of Economic Studies, 13:5, pp.4-15. Reprinted in Mark Blaug ed., Henry George (1839-1897): No. 34 in the Pioneers in Economics series, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar (1992), pp.256-67.

Sandilands, Roger J. (1992), ‘Savings, Investment and Housing in Singapore’s Growth, 1965-90’, Savings and Development, XVI:2, pp.119-44.

Sandilands, Roger J. (2015), ‘Rewards from Eliminating Deadweight Taxes: The hidden potential of Scotland’s land and natural resource rents’.

www.slrg.scot

Scottish Government, The (2015), Scotland’s Economic Strategy, Edinburgh.

Smith, Adam (1776), The Wealth of Nations. Cannan edn (1976).

SNP Manifesto, April 2015, p.14. http://votesnp.com/docs/manifesto.pdf

Thompson, E.P. (1991), Customs in Common, London: Penguin.

Tideman, Nicolaus (1999), ‘Taxing Land is Better than Neutral: Land Taxes, Land Speculation and the Timing of Development,’ in Ken Wenzer (ed.), Land-Value Taxation: The Equitable and Efficient Source of Public Finance, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1999.